TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — Airplanes, rockets and engines: These are the technological achievements most people associate with engineering. But sharks?

Thanks to grants from the National Science Foundation, the NASA Alabama Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research and the Lindbergh Foundation, Dr. Amy Lang continues researching what designers of aircraft and underwater vehicles could learn by imitating nature’s design of shark skins.

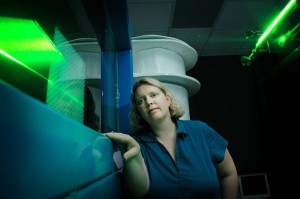

During the past two years, Lang, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering and mechanics at The University of Alabama, has researched how flexible shark scales can lead to the formation of embedded vortices between the scales in areas when the flow is about to separate from the shark’s body.

This could lead to increased maneuverability and reduced drag. Lang, like others, is convinced that evolutionary adaptations of shark skin structure have developed boundary layer control mechanisms. She hopes to apply her findings to aircraft and underwater vehicles.

The grants total $251,581 and will allow for the purchase of additional equipment and models. Previous work confirmed the formation of the embedded vortices, and the new grants will focus on mechanisms within the bristled shark skin geometry that lead to separation control, decreased drag and increased maneuverability for the shark.

“Most importantly, we now have a NSF collaborative grant with biologists,” said Lang. “This allows us to work with real shark skin, rather than simply models.”

Lang is collaborating with Dr. Phil Motta, professor of integrative biology from the University of South Florida, and Dr. Robert Hueter, director of shark research for Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Fla.

The project provides real shark skin that can be studied, allowing for a better understanding of the bristling mechanisms and the microgeometry of scales, and that allows the researchers to achieve a more accurate biomimetic model for fluid dynamic testing. Biomimetics is a term that sometimes refers to human-made designs that imitate nature.

Future studies will focus on separation control experiments of both shark skin models and real shark skin samples in UA’s water tunnel facility in Hardaway Hall.

These innovations in research provide the opportunity to discover new, passive, bio-inspired boundary layer control methods to decrease drag, and that would improve performance of submarines and aircraft through increased fuel savings.

The results of the research will be incorporated into educational outreach programs and exhibits at the Mote Marine Laboratory of Sharks in Sarasota, Fla., and at the McWane Science Center in Birmingham, Ala.

“Outreach through these two programs should educate more than 700,000 people each year about the drag-reducing properties of shark skin,” said Lang.

In 1837, The University of Alabama became one of the first five universities in the nation to offer engineering classes. Today, UA’s fully accredited College of Engineering has more than 2,700 students and more than 100 faculty. In the last eight years, students in the College have been named USA TodayAll-USA College Academic Team members, Goldwater scholars, Hollings scholars and Portz scholars.

Contact

Amanda Coppock, engineering student writer, 205/348-3051, alcoppock@crimson.ua.edu; Mary Wymer, engineering public relations, 205/348-6444, mwymer@eng.ua.edu

Source

Dr. Amy Lang, assistant professor of aerospace engineering and mechanics, 205/348-1622, alang@eng.ua.edu